Robert Altman’s 1992 film, The Player, stands as a scathing satire of the Hollywood film industry, brilliantly employing self-reference and semiotic elements to critique its own subject matter. By intertwining these techniques, the film becomes a metatextual exploration of the complexities of representation, reality and the constructed nature of meaning in cinema.

Self-Reference as a Critique

The Player is rife with self-referential moments that underscore the artificiality and performative nature of Hollywood. The film’s protagonist, Griffin Mill, is a studio executive who finds himself entangled in a narrative that eerily mirrors his own life. This mirroring of reality and fiction serves as a sharp commentary on the blurred lines between the two in the film industry. Mill’s life becomes a script, and his actions, decisions, and even his morality are dictated by the same commercial pressures and superficiality that govern the films he produces.

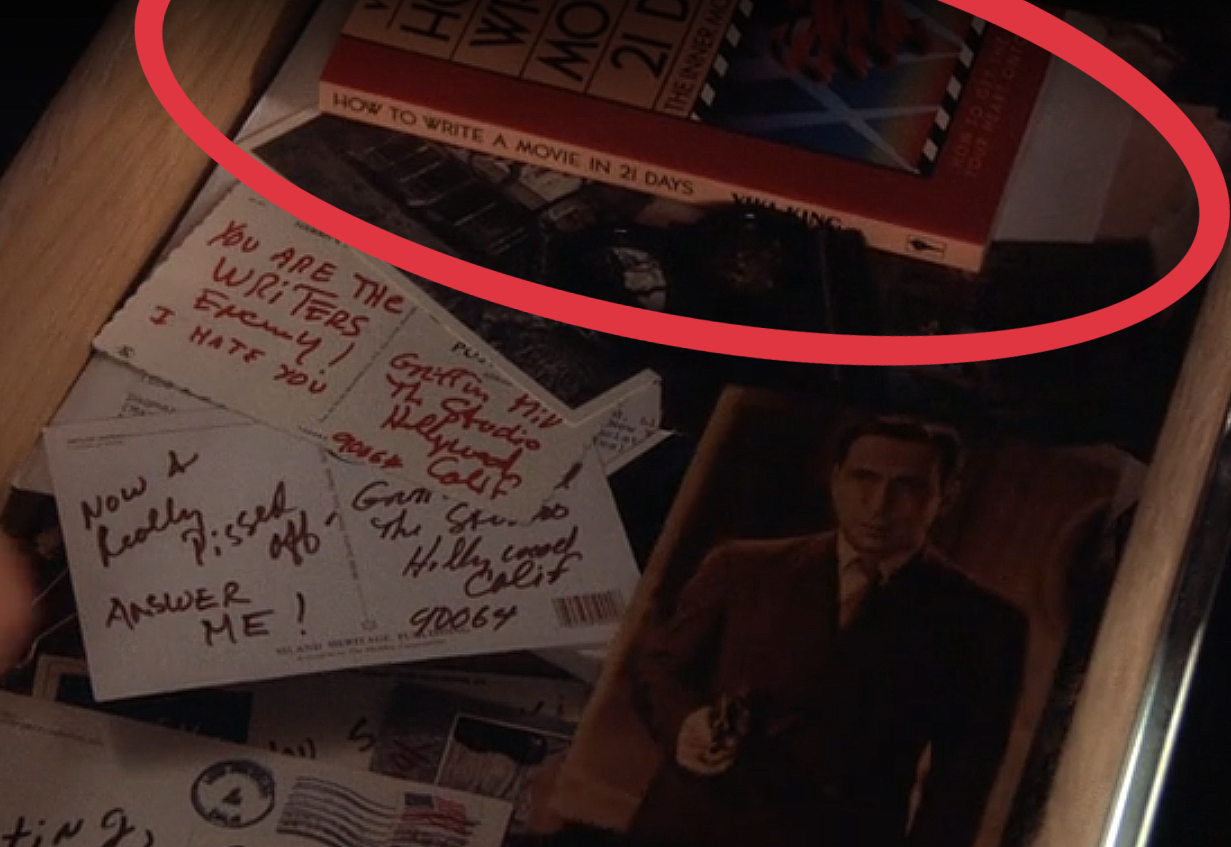

Moreover, the film’s narrative is filled with references to classic Hollywood films, such as Casablanca and Chinatown. These nods to cinematic history do more than pay homage; they suggest that Hollywood is trapped in a cycle of repetition and nostalgia, endlessly recycling its own myths and narratives. Mill’s desk drawer (where he stashes the “poison pen letter” postcards from his stalker) even contains a copy of How to Write a Movie in 21 Days by Viki King, suggesting that he has his own ambitions as a screenwriter, but is only referencing a formulaic guide to creating scripts, rather than attempting to gain a full education on the subject. Altman’s film thus becomes a critique of an industry that is both self-obsessed and creatively stagnant, constantly looking backward rather than innovating.

Semiotic Exploration of Hollywood

From a semiotic perspective, The Player is a dense text that plays with signs and symbols to critique Hollywood’s culture. The film’s very structure is a commentary on the art of storytelling. Griffin Mill’s job involves interpreting scripts—sign systems in themselves—and deciding their fate. His life becomes an extension of his work as he manipulates the reality around him to avoid the consequences of his actions. This overlapping of professional and personal life becomes a semiotic exercise, blurring the distinction between “real life” and “scripted life” and questioning the authenticity of both.

The numerous cameos by real Hollywood stars playing themselves further complicate the semiotic landscape of the film. These appearances create a dense web of intertextuality, a hallmark of semiotic analysis, requiring the viewer to decode these signs to fully grasp the film’s commentary. The audience is made aware that they are watching a constructed narrative about an industry that constructs narratives, pulling them into a self-referential loop that mirrors the film’s own critique of Hollywood.

Postmodern Values and the Blurring of Reality

The Player is also a quintessential postmodern film, characterized by its self-awareness, irony, and deconstruction of traditional narrative forms. The film deliberately eschews a conventional moral stance, leaving viewers in a state of ambiguity. Griffin Mill, despite his moral failings, faces no real consequences by the film’s end. Instead, he is rewarded, highlighting the cynicism often associated with postmodern narratives.

The film’s ending, where a script that mirrors Mill’s own life is pitched and accepted as a new movie project, further cements its postmodern credentials. This circular, self-referential structure challenges the idea of a linear, coherent narrative, instead embracing fragmentation and multiplicity. Life imitates art and vice versa in a never-ending loop, where reality and fiction become indistinguishable.

Additionally, the film’s pastiche of different genres and its intertextuality—blending various cinematic styles and narratives—are indicative of postmodernism’s tendency to mix high and low culture, often with irony or playful subversion. By doing so, The Player questions the very nature of storytelling and the role of Hollywood in shaping and distorting reality.

Conclusion

The Player is a masterful example of how self-reference, semiotics, and postmodern values can be employed to critique and deconstruct the very industry it portrays. Robert Altman uses these techniques to create a film that is not only a satire of Hollywood but also a deeper exploration of the complexities of representation and the constructed nature of meaning in the realm of movies. Through its self-referential moments, semiotic depth, and postmodern sensibilities, The Player invites viewers to question the reality presented to them, both on-screen and off.